At the University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics, Schreiber lost consciousness, prompting a staff member to contact his brother, who instructed the hospital not to resuscitate him, except for pain relief.

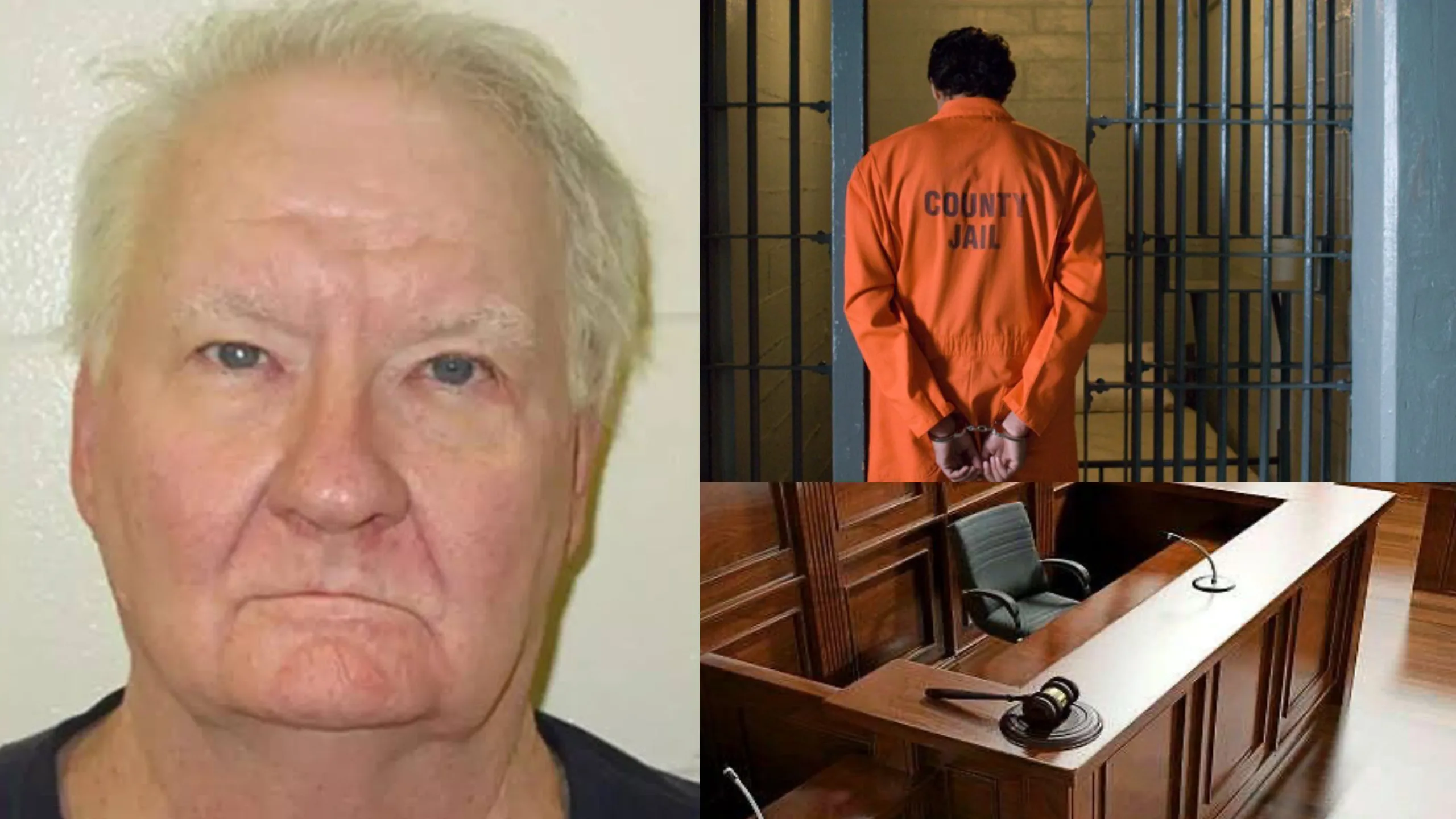

The prisoner, Benjamin Schreiber, presented his case to an Iowa appeals court, asserting that his brief death in 2015, followed by revival at a hospital, fulfilled his obligation to the state, and he urged the panel of three judges to allow him to move forward with his life.

However, the judges dismissed his argument, affirming a lower court’s decision to reject his petition.

Judge Amanda Potterfield, writing for the court, reasoned that Schreiber’s status was clear-cut: either he remained alive, necessitating his continued incarceration, or he was truly deceased, rendering his appeal irrelevant.

Despite Schreiber’s assertion that his sentence had ended due to his resuscitation against his wishes, the court upheld his life without parole conviction for the murder he committed in 1996.

Schreiber, 66, convicted of murder for killing a man with an ax handle, has pursued numerous unsuccessful appeals. In 2018, he contended in court that his resuscitation against his will meant his sentence had expired.

In March 2015, Schreiber, detained at the Iowa State Penitentiary, was hospitalized for seizures and a high fever caused by large kidney stones leading to septic poisoning.

At the University of Iowa Hospitals & Clinics, Schreiber lost consciousness, prompting a staff member to contact his brother, who instructed the hospital not to resuscitate him, except for pain relief.

Despite his brother’s directives and his own do-not-resuscitate order on file, Schreiber was revived. The courts have not addressed whether this resuscitation was wrongful.

Judge Potterfield emphasized that the term “life” lacked definition in the state’s code, leading the court to interpret it literally, thereby mandating that Schreiber serve the remainder of his natural life behind bars.

The court found Schreiber’s argument unconvincing, doubting that the Legislature intended to release criminal defendants due to medical interventions during incarceration.

Schreiber’s plea mirrored a similar case involving Jerry Rosenberg, convicted of murdering two New York police detectives in 1962, who unsuccessfully petitioned for release in 1988, claiming he died during surgery.

Professor Eve Brensike Primus of the University of Michigan Law School noted the rarity of such arguments, citing the alignment required between the individual’s medical condition and sentence.

She warned of the legal and logistical complications that would arise if individuals were considered legally dead prior to resuscitation.

Harvard Law School professor Glenn Cohen deemed Schreiber’s argument clever but ultimately untenable, as it blurred the distinction between life and death within criminal law.

Despite Schreiber’s assertion of being “dead” for the purpose of serving a life sentence, he would still be legally alive for matters such as organ donation, undermining his claim.

share this ost and drop your comment below!